Besides serving next to a black Jones who insisted on calling me his brother, I also served alongside a young man from New Jersey who went mostly by his given name. His family name was an odd collection of consonants. Every so often we had formal roll calls. The company would be ordered to fall in. The sergeant in charge would march swiftly to the center of the formation, turn smartly and begin calling names in a military staccato. His pace was matched by a practiced and rhythmic "Here!" coming from different parts of the formation. Name — Here!, Name — Here!, Name — Here! My Polish comrade-in-arms was an unexpected land mine for a young NCO finally in charge. At first light one icy morning, summoning his most manly, most authoritarian voice, he called, Name — Here!, Name — Here!, Name — Here!… Until he tripped over the cadence. In that split second, based on a lifetime of complications and confusions surrounding his name, my friend yelled, Here! And the roll call continued. It continued after the laughter subsided.

The first unanticipated problem I had with my name in French was that J is G. That is, the letter J is called G and the letter G, after a fashion, is called J. Not an enormous problem, I suppose, just a simple substitution. A lot like Alpha, Bravo, Charlie. The real problem was the seemingly innocuous letters that follow. The French were baffled by the ones. The French either do or don't pronounce the ending letters of words. That's the closest I can come to a hard and fast rule. In deciding whether to pronounce or not to pronounce, being a native speaker of French puts one at a distinct advantage. My mother-in-law's method for helping me learn which was which was to have me pronounce everything with or without the ending several times out loud until I realized which was correct.

Of course, ones presents no problem for a native speaker of English. Either it's ones, as in ones and twos, with an understood w in front of the o, or it's ones, as in Jones, with an understood w squeezed in after the o. But, in French, it might be pronounced something like own (the s being silent) or oh nez (the s becoming z) even oh ness (giving it a sort of Spanish flair). But, combining those with the J or G of Jones presents an unexpected range of alternatives. It could start with the sound of ge in edge and produce Joan, which doesn't sound right. Or, Joe Nez, which for some reason seems only tentatively acceptable. Joe Ness. Wrong again. Hoe Ness might work, if I came from Madrid. Using the same ge from edge, but eliminating any vowels, adding only n and z, produces Jnz, the sound I learned to produce in that momentary pause where they wondered what to do with this jumble of letters they were presented with. And that made things easier. But the French aren't as easy as all that. When I came back for my laundry, and when after a few visits I was finally recognized as being that pleasant young man who smiled and nodded more than most, I was greeted with, "Ah, Monsieur Onaise." And so I became, and so I was, for the duration of my tenure as a Pole in Paris, that nice young man Évon Onaise.

I was easing a block into place, concentrating on center of gravity and lifting with my legs — I'm not young anymore, so I tend to be more careful than people in their twenties — and what I thought might be a tiny incident turned out to be a booming fart. "Dees gus ting," he said, making a face. "What," I demanded, "Mexicans don't fart?" "No," he replied, cutting an enormous fart of his own. "Dey do dees."

In the Army there were lots of Joneses, though most of them, in my experience, were black. I worked with one who had enough personality for two. He introducing himself as Jones, though we all had embroidered names on our uniforms, mostly so he could turn toward me to say, "And this here is my brother Jones." It was fun to watch how people did not respond to that. He'd stroll into the office, pat me on the back and ask, "How's mom?"

My family had no choice about being Joneses, but they did have choices about first and second names. They chose rather ordinary names, I think. They named their children after Prime Ministers, movie stars and sometimes themselves. My own name was the single most common name in Wales when I was born. Thankfully, here it was a rarity. I was sometimes embarrassed to give Jones as my last name, as though I might be on the lamb or something, but the moment I said Evan Jones I was exonerated. It had a certain something about it that seemed honest. When people, many of them Joneses, yelled at their kids in the market, they never once yelled at me.

I had tea with the poet Basil Bunting in his temporary home when he was a visiting honorary professor at U.C. Santa Barbara. I was there hoping to photograph him and hoping as well to squeeze out some gossip about Ezra Pound and Luis Zukovski. What I got instead were stories about Russian aviators in England during the First World War with rainbow dyed beards. When he put my first and last names together he laughed and laughed and broke into a story about the British Census Taker in Wales. He worked his way down a series of row houses and the man of the house, door after door, was Evan Jones. He began to think these Welshmen were having a laugh at his expense. Finally, he demanded, "Is everyone in this town named Evan Jones?" "Oh, no," came the reply in a lovely Welsh lilt, "William Williams lives just across the way."

The first of everything is golden — our first step, the first articulate word we utter, the first kiss we experience.

The first thing I learned in Paris took place on the third floor of the Hôtel Danemark. I arrived Christmas morning near dawn. It was something below zero and the streets were covered in slush and almost deserted. In my hand was a scrap of paper with the address of a trustworthy hotel within walking distance of the Gare du Nord. A friend in Denmark had pressed this in my hand before I left with the advice that I should not trust taxis. It wasn't much, but it was all I had.

The next morning there were more cars and people on the street. I made my way through the Métro to La Coupole, the famous restaurant bar, in Montparnasse. I never once considered going inside. I'm sure I had less than the price of dinner in my pocket. I stood there for the longest time imagining Sartre with his pipe and odd eye scratching the incomprehensible into tiny notebooks. My journey began there because the Alliance Française was a short distance north, or down, or vers la Seine, where I was scheduled to study French. Between La Coupole and my ultimate destination, not far from the Rodin statue of Balzac that glowers at oncoming trafic, I saw an image that seemed predestined — a sign that read, Hôtel Danemark. I summoned my courage and registered for a room.

I looked for the Hôtel Danemark on the Internet recently and was shocked to find that it's still there, utterly stunned to discover that today it's a charming hotel with Italian marble bathrooms, specializing in English language tourists. My first thought was, they must have torn it down and replaced it with something capable of supporting marble.

When I walked in, the man who ran the desk, the man I suspected might own the place, appeared after an enormously long wait, more than long enough to discourage me from registering. He had the air of someone who had just been torn from the winning goal, or the details of a televised scandal. He managed, at last, a pained, but polite stare. I suppose you could count this as learning, but the truth is, I wasn't quite sure what I had learned or if I was learning anything at all. The hotel, this peculiar man, the language, the exchange of strange notes and stranger coins, the spiral staircase with room for no more than one, the portable bidet, the WC down the hall, and the paper thin walls, were a wonderful — perhaps wonderful is not quite the word — mystery to me.

It was later that day, the day after Christmas, my first full day in Paris, that I learned something I was capable of understanding. The front door — I suppose I call it the front door out of habit. The only door — there was no bathroom door, no closet door, because there was no bathroom, no closet. There was a small table near the window, an uninteresting chair, the portable bidet, a sink with occasional hot water, and a bed. But they were in Montparnasse. I was in Montparnasse. I was walking in the footsteps of Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Man Ray, Henry Miller. The room seemed perfect. Except the door. It didn't lock. It bounce back when you tried to close it. It didn't lock. It didn't latch. Either I had missed that chapter in all the stories about Paris or else the door was broken. I agonized over this before spiraling down the staircase to the front desk.

I received, I think, the iciest stare of my life, and I had just spent two years in the military. He disappeared for a moment and then reappeared with something like a tool box, in fact, a wooden box with a rope handle filled with tools. I followed him up the staircase, past the WC, down the hall, to my room. I dumbly pointed at screws and nuts eager to help, desirous of improving international relations. Finally, it occurred to me. I rushed to a phrase book and recited, "Est-ce que je peux vous aider?" May I help you.

He dropped a tool in the wooden box and smiled. I had obviously managed a connection. He grabbed me by both shoulders in a manly way and backed me up to the bed, where he forced me to sit. He held me like that for an uncomfortable length of time before saying, "Oui." Then he added the first thing I learned in Paris, something I have never forgotten. Very calmly, very clearly, he said, "Moralement." I could help him a great deal if I just did nothing.

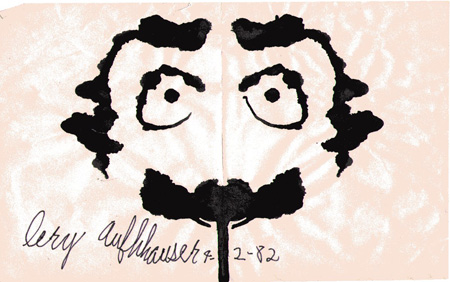

I got lots of milage out of this one. What was I thinking? What was I feeling. What was I trying to express?

I had a pair of broken glasses. The right stem came off, and without the rest of the glasses to go with it, it seemed rather interesting. I dipped the part that wraps around the ear in a bottle of India ink and then spun the other end between my fingers allowing the irregular end to flop about on a thick block of water color paper. When the ink was almost dry, I ran a light wash over the background. It took some of the ink with it.

I wasn't thinking about anything. I wasn't feeling anything beyond curiosity. I wasn't trying to express anything. I was just wondering what would happen. I watched the stem bounce around leaving traces of black. It was spectacular for a few moments under bright light. I can see it happening at a distance of forty-eight years. I watched an image appear. Not an image, exactly. A something. Which I emphasized with the wash. I think of it as fake art. Perhaps a great deal of what we most love is fake. Perhaps by fake I only mean random. And perhaps by random I mean something done but not quite understood.

I kept it on the wall for a long time, before the urge to fake other things, or to watch them emerge suddenly as if from nowhere replaced it. Somehow it ended up in a box with other things, and somehow it persisted. I'm thinking how amazing that is, and feeling how wonderful it is to discover things in old boxes that aren't merely junk. I'm trying to express that now.

My first serigraph. I was sixteen or seventeen when I did this. Across the street from my best friend's home in San Pedro were two women who lived together. They were probably in their early thirties, though at that age they might have seemed old at twenty. One was an artist and former nun who had studied under Sister Mary Corita. I knew about Sister Corita because my family owned a small serigraph she did on the subject of Tobias. David Davis, our interior decorator, purchased it sometime in the late 1950s. He had it framed to precisely complement an arrangement of pictures in the living room. He told us all about her. He was a Catholic and met Sister Corita while studying design at UCLA. So, my first knowledge of Sister Mary Corita, later Corita Kent, the quiet spokesperson for the 60's came from David Davis of Kurt Wagner Interiors.

The artist half of the couple taught me the rudiments of the process, allowing me now and then to assist her as she worked. I hung things up to dry and handed her the next appropriate sheet. It was a delightful combination of fun and purposefulness for me. Later, she gave me time and materials to myself, the first results of which you now witness. The other half made tea and told stories. She talked about poetry and philosophy, comparative religion, and the history of the trinkets that filled their tiny home. What I wouldn't sometimes give to be a happily adjusted lesbian. They were wonderful company. There were no latent sexual vibes, as I might have describe it then. It meant I could enjoy them as women without having to worry about being in the company of women. They were the most people people I knew at the time. Fascinating people.

The snows of yesteryear.

In the same box with the concrete poems or typewriter art of the previous post were some scraps from a project I did for a local church. I submitted sample pages in different styles, intending to do the project in the style they chose. These were among the styles they rejected. Maybe there were two projects, I can't remember. But, I do remember it ended up being several pages, stitched with card stock and then wrapped in handmade paper. Unfortunately, I also remember they wanted something more like block letters so they could read it. There's a reason television requires no insight and no training to watch. It looked like a Parents Day gift from the elementary school when it was done, except the paper was more expensive, and the letters better spaced. They weren't sure about the paper either. One of them asked, "How come it's not white?" In general, doing business with churches is not the best idea. The stupidest person of the bunch is usually its leader, and if not the leader, then the head of whatever committee happens to be in charge. "This Christmas we're going to decorate the church in red and yellow, because I decorated my house in red and yellow, and I really like it. It's stylish." And she donated how much last year?

If I were doing this again, I'd do it differently. I'd probably use a computer, since handmade things look woefully inaccurate today. Most things are like that. The letters were made with a witches' pen, sometimes called a poster pen, though there are numerous kinds of those — a piece of metal folded over with tiny holes along the bend. It has nothing sharp to catch the paper, like a pointy nib, so it can be pushed in any direction, even tilted and twisted, as the stroke is made. The ragged edges result from one side or the other of the nib losing contact with the paper. The ink tries to decide which way to go, toward the paper or back to the pen. I learned this technique studying the alphabets and writing samples of Arthur Baker that were published in the seventies and early eighties. His fonts, which are mostly pen based, are available at MyFonts.

I'm not sure what congratulations were in order, or what they were praying for, but it reminds me of a Sunday school story about a church missionary. I'll call him Dr. Johnson. The Sunday school teacher asked her class to write letters to their missionary overseas. But, she explained, Dr. Johnson has a great deal to do, so the letters should be short and not filled with questions, because if Dr. Johnson has to read and then answer all the letters, he won't have time to do his missionary work. A girl in the class wrote, "Dear Dr. Johnson, We are praying for your mission, but we are not expecting an answer."

I lived in a creek side house twenty years ago where visitors from the south of France ended up in a spare bedroom for a few days. After they rested from the flight, around ten that night they walked into the kitchen to find something to eat. The kitchen had a large light box covered with a sort of grayish mass of moving Daddy Longlegs. The next thing we knew they were screaming, hands in the air, running out the back door. To think they had come all this way only to be swarmed and eaten by huge American insects. To us, it was only that time of year when the Daddy Longlegs moved indoors for a while, ate mosquitos and disappeared. Reluctantly, we went to the closet, pulled out the vacuum cleaner, disrupted a local life cycle, and the Frenchmen stepped gingerly over the threshold.

I suppose one could feel the same way about frogs.

I don't believe in Astrology. Not the kind that says, because I was born on a particular day in a particular place I should expect the unexpected, be cautious in business after 12:00, look for true love at 5:00. It seems odd that Astrology has nothing to say about taking vitamins, eating lots of vegetables or getting enough fresh air and sleep. As if the stars are oblivious to such things. There was, however, that lady in pink capri pants at the market a few nights ago — probably an unrelated story. Still, it might be nice to know where and when such things were about to happen so you never missed anything. The sort of Astrology I do believe in controls, at least influences, the great cycles, the ones humans have difficulty grasping. Our lives are so terribly brief. A great deal of our culture is based unknowingly on Astrology.

My son Christopher found and saved my Birth Certificate from a pile of things set to be thrown away. Unless things relate directly to my father, they are of no interest to him. He has often done things for others, but with a secret withheld. The secret, of course, is how they benefit him, or how much in the long run they will end up costing you. You might object that I am related to my father, before wondering if you overstepped the mark. I look enough like my father to make that question moot. I am my father's son in every way that is not moral or ethical. Hard to imagine how I became my mother's son. Imagining her submitting to conjugal relations stretches credulity. Still, there must have been a time.

Anyway, there in that pile of things was a piece of paper my son found very important — his father's Birth Certificate. He is now its guardian. I know now, because of an accident that seemed predestined, that I was born at 1:09 in the afternoon, June 26, 1945 — a fact that had long eluded me. With the help of Google, I found my coordinates, and with that I became a full-fledged chartable subject.

I share a birthday with the United Nations, as I discovered some time ago. It was signed into existence in San Francisco the day I was born. Long Beach is only 500 miles south of San Francisco. So, in theory, other than age, of course, we have things in common. We both turned out to be somewhat ineffectual. Wars rage and the United Nations chitchats about the weather. The same wars rage and I write posts about Astrology. Other than that, and our taste in Architecture, I can't think of anything we have in common.

For the record: June 26, 1945 1:09 PM 33° 48' 15" N 118° 9' 29" W

It seems terribly insufficient for summing up an entire life — genes have the decency to be unnervingly complicated. Date, time and place. Less data than a single line. However — it amounts to grasping at straws — my hope is that the date and time of the signing into existence of the United Nations was based on some unfathomable, yet valid system of Astrological analysis. Such that, somewhere in the great scheme of things, it turns out finaly that each of us was a magnificent idea whose time had not yet come.

A dishonest pastor is bad enough, but a dishonest pastor who has not done his homework is the worst of all. When I think of Easter, I think of two stories. There's a third that sometimes creeps in as I'm telling the other two. Many years ago I attended a church because my uncle and his family were active members. It had a temporary pastor when I arrived. My uncle was keen on finding a permanent one. He rose to address the question at a church meeting, faltered, sat down and died. In a sense, it was the perfect ending. The man he was about to suggest was contacted and eventually hired. Of course, my uncle wasn't there to interview him for the job or to follow his exploits. After the new pastor arrived, I continued attending. Eventually, I attended mostly as an act of solidarity with those seeking to remove him.

Preying on widows has a long and almost Biblical history. He was quick to calculate the financial status of my aunt and just as quick to make sure she stayed on as treasurer, where she could make up deficits with personal checks and authorize his expense vouchers. He was a piece of work. One Sunday he warned us to keep our eyes out for people in brown robes, because he heard something about a Buddhist church looking to buy property for a retreat center. We were to follow them closely, if they showed up, to make sure no one buried anything like statuettes of Buddha. "That's how they claim territory," he explained, "for the devil."

Anyway, his first Easter sunrise service was memorable. He had a platform built on the hillside next to the church with a cross beneath it. The cross was staked out and dug into the ground, and required an entire pickup load of white blossoms from trees then in bloom to fill. If Reverend Schuller could do it, so could he. He had widening horseshoe rings chalked into the parking lot with individual spaces marked out so people could attend Easter sunrise service from the comfort of their cars. A small ocean of folding chairs was placed in front of the cars and below the platform. There were speakers pointing in all directions, huge speakers pointing toward the cars. Unlike Reverend Schuller's first drive-in church, there were no speakers to hang from the windows, no radio signal, just chalked in horseshoes, loudspeakers and a self-important pastor.

The second wealthiest member of the congregation was a successful contractor who was more supportive of his wife's membership in the church than his own. The pastor's idea was to buoy him up, make him more important. He felt no need to be more importance than he already was, but the pastor took him aside shortly before the service and said, "I want you to give the invocation." The contractor held his hands out saying, "No, I don't pray in public." The pastor said, "Sure you do." After all, wasn't it the greatest honor in the world to be selected?

That year's sunrise service was scheduled for 8:30. The idea was — I'm guessing — not to inconvenience anyone. Also, I suppose, to give the sun plenty of actual time to rise. The preparations were excessive, to say the least. There was a building project for the platform, the purchase of expensive sound equipment, flowers, chalking the parking lot, fliers — all for a church of perhaps forty members, counting a few who had long since moved away. By 8:30 there were two cars in the horseshoed area and a smattering of people spread out in the seats. The same twenty or so who always attended. The pastor walked onto the platform. He was wearing a white robe no one had seen before. He made the announcement about the invocation, but the contractor didn't budge. After a few uncomfortable stares and gestures, the pastor made his way down the hill and they talked for a while. Slowly, the contractor trudged his way up the hill, onto the platform, positioned himself in front of the microphone, and with eyes open, head held high, he said, "The Lord is risen. Amen."

After that, we might easily have gone home.

The story I'm reminded of at this point took place at the Norbertine Abbey down the road. I went with Bob Myers as often as I could. They were allowed to say Mass in Latin. We sat in the heathen section, as Bob called it — the back row where you could kneel or not kneel without calling too much attention to yourself. Bob died a few years after we moved. Father Parker, the founder and retired Abbot died a few months ago. He was the genuine article. A polyglot, he frequently translated his homilies or remarks into the language of visitors, switching effortlessly from one to the next. They came from everywhere. He spoke slowly and in an accent that was thick and difficult to place. On the Sunday before Easter, before the celebrant that day dismissed us, Abbot Parker made his was to the lectern for one final remark. A man of infinite patience, a man who had seen and heard it all a dozen times over said, "By the way, Easter sunrise service this Easter will be at sunrise."

It was the following year that the second story took place. The pastor, who by then had become the Reverend Pastor, showed up inside the church this time wearing a new suit, brand new cowboy boots, a bright silver buckle, and a stole or something over his shoulders that no one could remember seeing. As always, he wore his enormous silver and jade cross that had vague stories and miracles attached to it. In the course of his sermon, which was not interrupted or postponed by the recalcitrance of a wealthy congregant, he intoned on heathen Easter traditions. New clothes were a heathen tradition, despite the no expense spared look he presented. Easter bonnets, Easter eggs, Easter candy, Easter bunny. None of it was Christian. "There is only one truth to Christianity," he allowed in an odd mixture of precision and obscurity. Then his tone changed. He said, "Now don't you be going home and telling your kids the pastor says they can't have Easter eggs or chocolate, and don't be telling them the pastor said they can't get dressed up and have fancy dinners, and don't be telling them they can't have fun, because that's not what I'm saying. All I'm saying is, if you're going to partake in these heathen traditions, and I know you are, then make sure they know what Easter is all about. Make sure they understand that Jesus died on this day for their sins."

I found these at the grocery store last night. There was a red sale sticker on the shelf. I wonder why. They are part of a deck called the "ECO EDITION" and carry the following:

OUR PLAYING CARDS ARE CRAFTED FROM

SUSTAINABLE FOREST PAPER,

STARCH-BASED LAMINATING GLUE AND

VEGETABLE-BASED PRINTING INKS.

THIS PACK OF CARDS IS RECYCLABLE.

Recyclable, yes, but is it usable? It was amazing how long it took to pick these four particular cards from the deck. The Ace of Spades was easy — it was also on top — but the rest were almost impossible. I can only imagine the prodigious feats of concentration required to play a game at stakes with ranking suits. I increased the contrast so you wouldn't think I was exaggerating. In reality, they all look approximately the same. The secret message, I believe, is that recycling is for nitwits. Bicycle can now say they tried, but their customers resisted. I'm sure there are inks that approximate truer colors, but that wasn't the point. If they used those, no one would know the difference. No one would wonder what the hell was going on.

If this is the fate of recyclability, then give me red, black and white. Yes, that's the ticket. And don't bother updating those factories. It's a subtle ploy. Endorse green for the purpose of avoiding it. We should give credit where credit is due. They did their worst, and they succeeded.